Greetings!

During the frosty, dark nights of December, I always crave killer sweets. Sweets like chocolate marshmallow fudge. And glazed gingerbread. And cinnamon-sugared crullers.

And as I write the sequel to Fanny Newcomb and the Irish Channel Ripper—which takes place in 1889 New Orleans—I’ve been lusting after that city’s most popular killer sweet: creamy pecan pralines. (If you’re also lusting after pralines, keep reading. You’ll really like my December contest!)

With a vast local supply of sugar, New Orleans has never lacked for tasty sweets and beverages. In the Gilded Age, New Orleans households and cafes were especially celebrated for sweet drinks like ratafia liqueurs, cordials, crème syrups, and fruit punches. Not to mention absinthe.

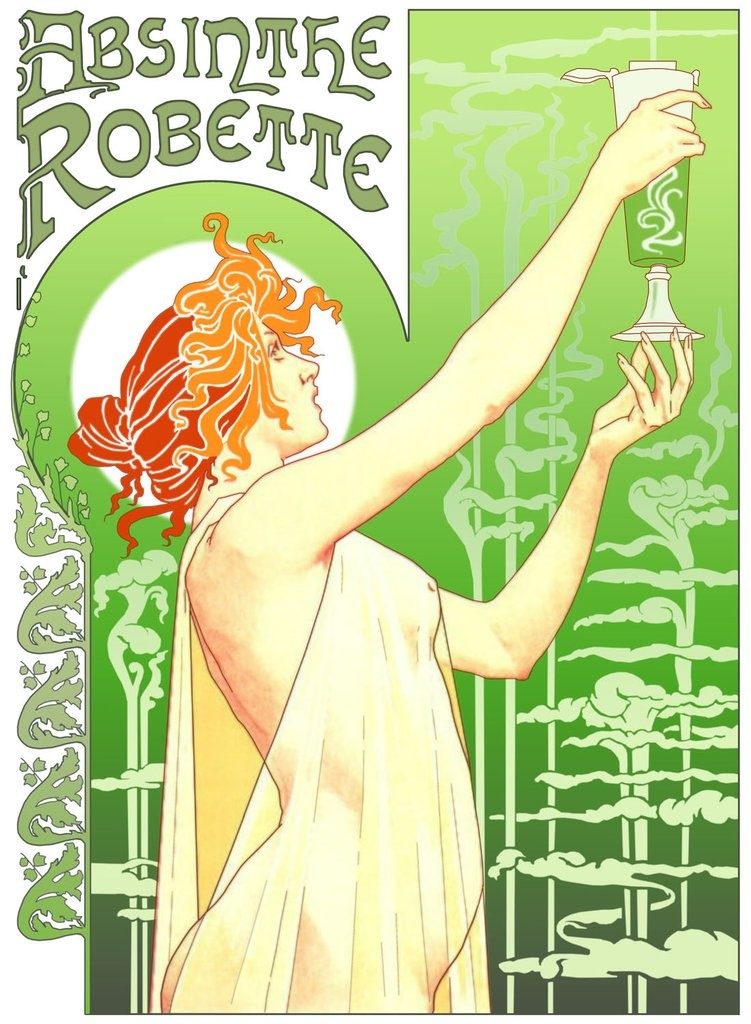

Ah, absinthe! Fragrant, floral, and highly intoxicating, emerald-colored absinthe was celebrated as the seductive green-eyed fairy. Drinking one glass almost always guaranteed hallucinations. Drinking two glasses or more…well, in that event, absinthe could be the ultimate killer sweet….it was to die for.

Absinthe Robette poster by Henri Privat-Livemont.

Distilled from wormwood (which is more tasty than its name suggests), green anise, and sweet fennel, absinthe has been around since the late 18th century. But the spirit really took off in the late 19th century when it was enjoyed and celebrated by French artists like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Édouard Manet.

As always in the Gilded Age, most things French quickly found a home in New Orleans’ French Quarter. Along with champagne, cognacs, and brandies, absinthe was imported directly from France into New Orleans. In addition, The Picayune Creole Cookbook provided recipes on the best ways to concoct absinthe ratafia, absinthe frappés and crème d’absinthe at home.

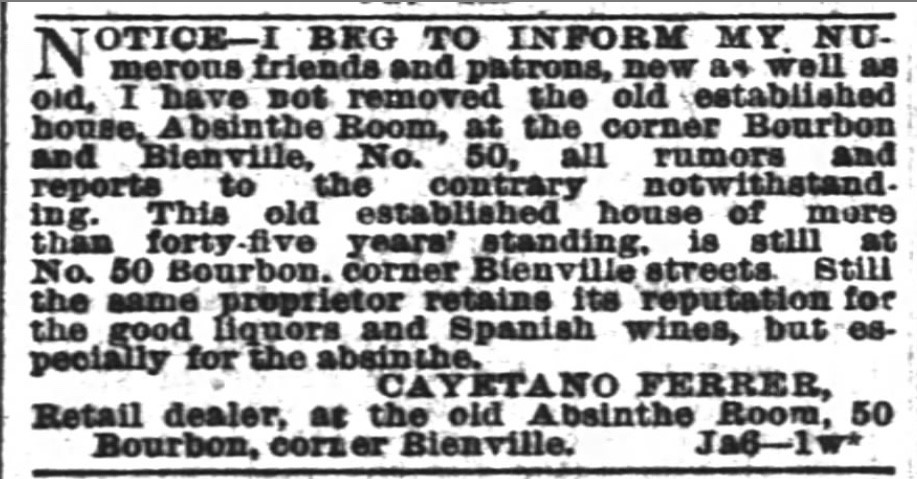

Mostly famously for New Orleans, the green-eyed fairy was served at the old Absinthe Room, which—as the 1882 advertisement below “begs to inform”—was located at the corner of Bourbon and Bienville Streets, or “No. 50 Bourbon, corner Bienville”.

The (News Orleans) Times-Picayune, Jan 10, 1882 via Newspapers.com

Absinthe served at the old Absinthe Room was diluted (quite theatrically, by using a tall absinthe fountain filled with chilled water) and seductively sweetened with a large sugar cube. But pure absinthe often contained 60 percent hard alcohol (such as rum or brandy), which put the sanity and lives of absinthe drinkers at great risk.

As a special correspondent to the Times-Picayune wrote in 1886:

“absinthism is a more serious and intense intoxication than that produced by any other alcoholic stimulant…. [The absinthe drinker’s] passion leads him almost inevitably to insanity, to softening of the brain or to paralysis. All of the senses are either weakened or subject to derangements of one kind or another….”

By 1915, absinthe proved so dangerous to drinkers’ sanity and health that it was banned in the United States, France, and other countries. Absinthe drinking was not legal in America until almost a hundred years later, when federal regulations enforced changes in the spirit.

Finally, the 19th century’s seductive killer sweet had been tamed for 21st century enjoyment, and today—just as it did during New Orleans’ Gilded Age—the Old Absinthe House serves absinthe at the corner of Bourbon and Bienville Streets in the French Quarter.

Now, back to pralines. If you love killer sweets as much as I do, please enter my December contest. The prize is a box of Evans Famous Creole Pralines from the Cafe du Monde in New Orleans. Now that’s a killer sweet!

Happy holidays!