by Deanna Raybourn

One of the joys of writing historical fiction is the chance to read as much as you like on a pet subject—so much that you could easily bore your friends senseless on the topic. (Inviting writers to dinner parties is a risky proposition.) Over the years, I have acquired a set of these subjects, the themes I return to over and over again, never tiring of sleuthing out the most minute details. Among my favorite half-dozen topics is the field of Victorian female explorers, the intrepid women who packed up their parasols and petticoats and roamed the world in search of adventure. Some were scientists, some artists, some unabashed curiosity-seekers who simply went out to see what they could see.

One of the joys of writing historical fiction is the chance to read as much as you like on a pet subject—so much that you could easily bore your friends senseless on the topic. (Inviting writers to dinner parties is a risky proposition.) Over the years, I have acquired a set of these subjects, the themes I return to over and over again, never tiring of sleuthing out the most minute details. Among my favorite half-dozen topics is the field of Victorian female explorers, the intrepid women who packed up their parasols and petticoats and roamed the world in search of adventure. Some were scientists, some artists, some unabashed curiosity-seekers who simply went out to see what they could see.

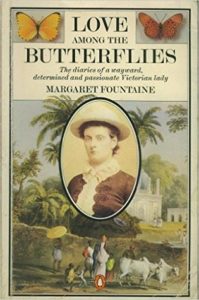

There are scores of these women–Mary Kingsley, Isabella Bird, Amelia Edwards, just to name a select few—but my favorite is one of the lesser known travelers, the redoubtable Margaret Fountaine. Born in 1862, Margaret was a product of the Victorian empire at the height of its achievements. She was a romantic soul, sometimes ludicrously so, and she felt keenly the restrictions of her solidly-prosperous, middle-class upbringing. She was artistic, dabbling in watercolors and singing before settling upon lepidoptery, the pursuit and study of butterflies, as her life’s work. When, at the age of 27, she achieved financial independence through a family legacy, Margaret took up her butterfly net and killing jar and set off or parts unknown, never to look back.

Her career spanned the better part of fifty years and took her to six continents. When she died—net in hand on a butterflying expedition to Trinidad—she left her collection of lepidoptera and her diaries to an English university with the proviso that the journals not be unlocked until 100 years had passed from the date she began to write them. A century after she first put pen to paper, the diaries were opened, revealing a series of surprises to the scholars to studied them. Not merely the record of her travels and specimen sketches, the journals were an account of her other collection—men. Margaret Fountaine, as it happened, was a very modern woman with very modern ideas about relationships between the sexes. Not content with pursuing butterflies, Margaret pursued love affairs, recording the kisses and caresses she exchanged with her traveling companions with startling candor. She related details of all her liaisons including her lifelong passion for her Syrian dragoman.

Reading Margaret’s journals—excerpted into two volumes from the original twelve—was a profoundly inspiring experience for me. Spanning the course of her life from teenager to elderly woman, they are witness to her fortitude, her resilience, and sometimes her silliness. She did not shrink from recording herself at her worst, and the diaries show this as well, offering up her bursts of neediness and pedantry, her snobbishness and tendency to manipulation. But seeing Margaret’s lesser qualities only serves to highlight her noble ones. She was courageous, both physically and morally, never shrinking from what she believed to be her duty. She wrestled with the ingrained expectations of her society, daring to question them as she made her own way forward, always choosing to be true to herself.

Reading Margaret’s journals—excerpted into two volumes from the original twelve—was a profoundly inspiring experience for me. Spanning the course of her life from teenager to elderly woman, they are witness to her fortitude, her resilience, and sometimes her silliness. She did not shrink from recording herself at her worst, and the diaries show this as well, offering up her bursts of neediness and pedantry, her snobbishness and tendency to manipulation. But seeing Margaret’s lesser qualities only serves to highlight her noble ones. She was courageous, both physically and morally, never shrinking from what she believed to be her duty. She wrestled with the ingrained expectations of her society, daring to question them as she made her own way forward, always choosing to be true to herself.

She was not always a likeable woman, but she was perpetually interesting, and it was Margaret who inspired my newest heroine, Veronica Speedwell. Also a Victorian lepidopterist by profession, Veronica too has a penchant for comely men. Unlike Margaret, Veronica is often sidetracked from her studies by the unexpected lure of amateur investigation. (Although I suspect Margaret would not have been able to resist a dead body or two…) As Margaret did, Veronica has traveled to the “loveliest, wildest, and often the loneliest places of this most beautiful earth,” collecting butterflies and forging her own path.

In creating a new character, it’s sometimes difficult to find a touchstone, a North Star that will always point you in the direction that character will travel. To know how a character will behave in any given situation is a necessity and a gift. When I struggle with how to direct Veronica, I have only to refer back to Margaret’s journals and her dedication to the readers who would discover them: “To the reader—maybe yet unborn—I leave this record of the wild and fearless life of one of the ‘South Acre Children’, who never ‘grew up’–& who enjoyed greatly and suffered much.”